Ordinarily, zooplankton and those larger animals then respire carbon dioxide back into the ocean. Most of the time, Raven said, zooplankton eat up the phytoplankton, then get eaten up by larger animals. In oxygen-rich oceans, the food web moves carbon around, starting with phytoplankton – tiny drifting organisms that get energy from the sun – that absorb carbon dioxide at the ocean’s surface.

The research was published in the journal Science. Now, Raven, University of Washington chemical oceanographer Rick Keil and Sam Webb, a staff scientist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, have joined forces – and scientific methods – to show that a different element, sulfur, may play a role in regulating the carbon cycle in low-oxygen areas. But what piques Raven’s interest is the changing chemistry of the oceans, the Earth’s largest carbon sink, and how it could move carbon from the atmosphere to long-term reservoirs like rocks. These strange ecosystems are expanding thanks to climate change, a development that is of concern for fisheries and anyone who relies on oxygen-rich oceans.

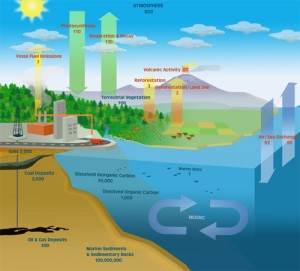

#CARBON CYCLE OCEAN FULL#

But although anoxic oceans may seem alien to organisms like ourselves that breathe oxygen, they’re full of life, she said. “You don’t get big fish,” said University of California, Santa Barbara biogeochemist Morgan Raven, or even “charismatic zooplankton” such as krill. With no dissolved oxygen to sustain animals or plants, ocean anoxic zones are areas where only microbes suited to this harsh environment can live.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)